Note (2023/5/9): I've changed my mind a lot since I wrote this, I believe I was naive regarding the statistics and the real mechanics behind social change. I will write about this in a future piece.

Hello everyone,

The world seems to be falling apart. At the risk of sounding completely delusional I must ask — is it really?

It was not long ago that the world's gaze was on bushfires ravaging Australia, and without time to recover the coronavirus has run rampant across the globe. We responded to the emergency across the world with measures unheard of, but we were able to slow down its spread and even flatten the curve of its increase. But in the heart of the lockdown the world was exposed to footage of the officer Derek Chauvin, pinning his knee on the local bouncer George Floyd's neck for a full eight minutes — even when he begged him to stop, told him he couldn't breathe and called for his mother.

The world went berserk, or at least it seems like it has.

Peaceful protests. Rioting. Looting. The burning of buildings. The abuse of state and military power.

And everything in between appears to have unfolded in response.

It was the straw that broke the camel known as civilisation's back — or so you would think.

The Banality of Goodness

I first heard this term uttered by the wonderful Matthieu Ricard in his TED Talk How to let altruism be your guide. Matthieu is a French-born Buddhist monk who was dubbed "The Happiest Man in the world" after neuroscientific studies into his brain. At age 25 with a PhD in Ethnobotany, he abandoned his promising scientific career for life as a simple monk and never looked back. What he was saying is simple: Goodness is so commonplace that it has become invisible, we take it for granted.

"Now look at here. When we come out, we aren't going to say, 'That's so nice. There was no fistfight while this mob was thinking about altruism.' No, that's expected, isn't it?"

"If there was a fistfight, we would speak of that for months. So the banality of goodness is something that doesn't attract your attention, but it exists."

Right now, you have the leisure of reading this letter. You probably are not worried about starving, and you probably are not in fear for your life. This is a truly wonderful circumstance.

"We take its gifts for granted: newborns who will live more than eight decades, markets overflowing with food, clean water that appears with a flick of a finger and waste that disappears with another, pills that erase a painful infection, sons who are not sent off to war, daughters who can walk the streets in safety, critics of the powerful who are not jailed or shot, the world's knowledge and culture available in a shirt pocket."

Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now

We take it for granted, but the way things have been is far from a guarantee in life.

"Part of the bargain of being alive is that one takes a chance at dying a premature or painful death, be it from violence, accident or disease."

Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of our Nature

The normal we are used to is also not the normalcy in nature.

“The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are being slowly devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst and disease.”

Richard Dawkins, The River out of Eden

Nor is it the normalcy in history.

"For most of human history war was the past time of governments, peace a mere respite between wars."

Steven Pinker

We are helpless but to fail to appreciate the peace in our lives because we have grown so used to it. Ironically, the very fact that we are quick to outrage in its absence is evidence for this.

The slaughter of one creature at the hands of another is ubiquitous in the natural world, and the death of man at the hands of himself is commonplace throughout all of history.

That we have reached a level of peace and stability that we can take it for granted is breathtaking in of itself. We have come so far that we continually fail to realise it, let alone feel grateful for it.

Two weeks ago in my letter On Cynicism I made the point that when we tell ourselves the world is going to hell, we are not in touch with what is actually happening. That when we grow cynical about the state of the world, we are comparing it with an ideal one of our creation, not a real one in history.

Given the entropy in the world — the natural tendency for things to fall into chaos — we should be grateful to be able to live in these times. To be cynical about this, to deny that we have progressed, and that there is something beautiful in the promise of civilisation is to fail to remember how life has been and a failure to imagine how worse they could be.

There is less violence and racism today

"If you had to choose one moment in history in which you could be born, and you didn’t know ahead of time who you were going to be–what nationality, what gender, what race, whether you’d be rich or poor, gay or straight, what faith you’d be born into–you wouldn’t choose 100 years ago. You wouldn’t choose the fifties, or the sixties, or the seventies. You’d choose right now."

Barack Obama

Years ago, I was having a conversation with a friend of mine. She was a wonderful individual and was passionate about addressing the problem of racism in society. She believed it was as much of a problem today as it has ever been. I disagreed with her here; this is clearly not the case. That despite the levels of police brutality, discrimination and aggression faced by minorities today — we have come a long way.

There was a time where lynching was the norm — a fun-filled day for the whole family. Grown men and women would attend these events with fascination, taking with them their kids, to watch the torture, mutilation and slaughter of their black brothers and sisters. Many would even feel compelled to take the fingers and hair of them to display in their offices and places of work. This was commonplace; it was the norm. It wasn't seen as strange at all; it was just the way it was. We didn't blink.

Today, the world has witnessed a single black man murdered at the hands of the police, and we have thrown our arms in outrage. There is less violence, and yet we are rightfully furious.

It is absolutely not acceptable that the people that are supposed to be looking after us are so callously slaughtering for alleged crimes as trivial as counterfeiting a twenty-dollar bill. Yet to say that we have made no progress on this front is simply untrue. As terrible as things seem, they are better than they have ever been.

These two statements are both true:

-

We have made tremendous progress politically and made strides towards a more peaceful and equal society than ever before.

-

There is still a lot to be done. Racism is still a serious problem. It is unacceptable that anyone's lives are treated so callously.

There is less racism — and racist violence — in society than there has ever been in the past. It is still a problem that there is any. We should look to its causes and work toward dismantling them. We can do all of this without denying that the work of those before has been fruitful.

The worry people have is that after the sentence the world is better than it ever has been, is an unspoken and therefore we do not need to improve it further. Under the mask of outrage is the fear of complacency. That there is a fight which we must take part in and we cannot afford to relax.

To me, this doesn't make sense.

It is a declaration that progress has never been made. To deny the success of those who have worked on these problems in the past — to assert that our hearts and minds have never shifted in the right direction — how could this possibly be motivating? How on earth is this inspiring?

Does anyone honestly believe that the work of those such Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King has done nothing to improve our circumstance?

Racism, violence, poverty and many other issues have been the occupation of many of those before us for generations. Working towards a better world is not a new and trendy thing.

The problems of the world — including racism, violence and poverty — have been the preoccupation of many passionate and brilliant people throughout history. We have been working to improve our circumstance since time immemorial — and we have surely succeeded time-and-time again.

By almost every measure we value, we are doing better now than we ever have been

Indeed, it is because we have worked toward improving our circumstance and have succeeded over and over, that we should have the confidence and inspiration that we can do it again.

Conversely, to believe that we haven't made any progress at all is to give in to fatalism. If we genuinely haven't made progress, is there any basis to hope that we can? If all that the brilliant and dedicated men and women before us have left behind is disappointment — what hope do we have to resolve it?

Rather than being concerned with the truth of what they were saying, people have been worrying about how it would impact those who heard it. A sacrifice of clear communication for public relations. This was an unnecessary worry and damaging strategy — we do not have to view the world as a hell to work toward making it more like a heaven.

Working towards a better future need not depend on pretending things have never been worse.

The Negativity Bias: A Defensive Mechanism

If progress is real, why is it that so many deny it? If we have made the world a better place and can continue to do so, why is it that we are so slow to acknowledge it?

We ignore, forget, filter out and take for granted all the good we witness in the world and hold onto the bad. We often do this under the pretense of seeing the world as it really is, accepting the cold hard truths, being a realist.

I have written about an interplay of biases we tend to have that fuel these tendencies of mind in my 2018 piece How far we have come.

Namely; the negativity bias, the availability bias and the confirmation bias.

The negativity bias is that adverse events are more salient in our memories. This is almost the psychological equivalent of the banality of goodness. The good in our lives fall into the abyss of the forgotten past, while we carry the bad with us wherever we go, our eternal cross to bear. I believe it is a defensive mechanism, we hold onto our pessimism and selectively remember that which validates it to protect ourselves from disappointment.

I wrote about it in the letter I sent out two weeks ago On Cynicism.

We do not sink into these lows because we are brave enough to face the cold truth, but because we are afraid to walk into an uncertain future. It is more comfortable to reassure ourselves that the world and the people in it are wicked, than to consider that they are a mystery. We pretend we know that the outcome will be adverse and brace ourselves, hardening our hearts in its anticipation — rather than realise that we indeed don’t know how things will play out. Somehow it is easier to bear telling ourselves that the worst is certain, than that there is genuine uncertainty in our circumstance.

In short; the negativity bias is that we selectively remember the ill and thereby frame our view of the future in that negative lens.

The availability bias is that we judge the probability of events based on how quickly they come to mind.

An example I've used before is the question: Do more words start with the letter "r" or have "r" as the third letter?

"Ring", "rain" and "rum" roll off the tongue and come to mind much quicker than "bird", "word" and "card".

Most people make the mistake that more words start with "r", but the truth is it is just that words beginning with 'r' readily come to mind. Recalling a word by its first letter is much easier than recalling it by its third.

The other example I gave was the question: Are people more afraid of driving or flying?

The answer is obvious. Most of us spend a lot more time in cars than in planes. A fear of flying is much more commonplace than a fear of driving — but it isn't justified.

When an incident happens on a plane – like a terrorist attack – it is broadcast on the news all over the world. When thousands die on roads every year, it simply becomes another statistic.

We can bring to mind more instances of plane incidences than that with cars; therefore we estimate that we are much more at risk in a plane — and we are wrong.

We mistake events that come into memory, for events that are more likely to happen. This is the availability bias.

The confirmation bias is simple. We are more likely to seek and remember information that confirms our existing worldviews than that which criticises it.

These three biases work in tandem. The negativity bias means that we remember the bad more than the good, as negative memories are more salient the availability bias means we are likely to see things as much worse than they are. The confirmation bias means we are unlikely to seek out or remember information that contradicts this.

This is made a lot worse by the media. As negative stories impact us more than positive ones, they are incentivised to publish them. More people are reading the news if they believe the world is in a state of emergency, or as they say; what bleeds leads.

This sparks a vicious cycle that I have written about before in that 2018 piece.

The Cycle of Cynicism

- The Negativity bias causes bad news to impact us more than good news

- The media industry depends on capturing our attention and is incentivised to focus on the most negative news

- All of us that consume the media now can much more easily recall bad things happening much quicker than we can recall good things

- Because of the Availability bias, we mistake the ease in which we can recall bad news with the actual state of the world as it is

- This solidifies our view of the world and other humans as bad, which causes us to be more likely to seek negative information to reinforce it, which starts the whole cycle all over again…

We know that it is getting better all the time. We have been improving our circumstance by every measure. We are wealthier, healthier, more peaceful, we discriminate against each other less, we are less violent, our self-reports of happiness are higher than they have ever been — and yet it does not feel this way. As we live in an ever more interconnected world, we are more aware of all the bad that is happening within it. We are exposed to more of the ills in the world, such that we fall to the illusion that it is getting worse. The world is steadily improving, but our standards raise time and again at an even faster rate.

I have come up with the rule that life seems to improve over time, but never at a satisfying rate. The positive changes we yearn for arrives, but at too slow a pace to inspire us. I made this rule up half-jokingly, but I believe we are playing elaborate games with our minds that render us blind to the very positive change that we yearn for. We continually succeed in improving the world, and we continually fail to acknowledge, recognise, be grateful for and even enjoy it.

A middle way to a better world

Back to the present: we are in the middle of a worldwide pandemic. Protesting, rioting, looting and military enforced curfews have been happening all over America. Protests in solidarity have been happening all over the world, and violence has erupted in the aftermath of many of them.

These events are not a reason to believe that progress has not occurred, that we are in the same place we have always been.

But acknowledging how far we have come, it does not follow that we do not take the problems in the world seriously.

If a single fellow being is suffering, we have a problem on our hands. We should be taking meaningful steps to resolve it.

The world shook at the sight of a police officer murdering a local bouncer in public, on camera. Why can't we leave each other alone? Racial Discrimination and Police brutality is a problem we have been living with for centuries. The deeper issues of division between ethnic groups and the abuse of authority have ancient roots that we must sever.

I have no doubt many people have been on the short end of the stick here and are understandably furious.

But what should we do about it? How do we go forward?

There are many answers to this question, and people are living out their own answers all over the world.

Some spend their lives undermining and criticising our systems, some integrate with them and work to change them from within. Some believe this needs to be a matter of improving governance and law; others believe it is the culture itself that needs to change first and foremost.

The US government is increasing its grip on authority and enforcing curfews. President Donald Trump is demanding law and order. Peaceful protests are happening everywhere — and there has been violence at some of them. There have been opportunistic looters and pundits that are claiming that this is a justified and necessary thing to do. There are decent police in the ranks — yet there are also countless filmed instances of police abusing and initialising violence against non-violent individuals.

The question on my mind is: Violence or non-violence?

There are real problems, there is real suffering, if there is ever a good reason for outrage here it is.

Even if the wild beast of anger is justified, it doesn't mean it is beneficial to let it run wild.

I believe it is now more than ever that we need to heed John Lennon and Yoko Ono's words and give peace a chance.

Erica Chenoweth is a political scientist that believed that violence was necessary for difficult political change. At a workshop advocating for non-violent organisation, she was challenged by the woman who would become her co-author Maria J Stephan. Maria challenged her to look at the historical data and prove her tragic intuition that violence was necessary.

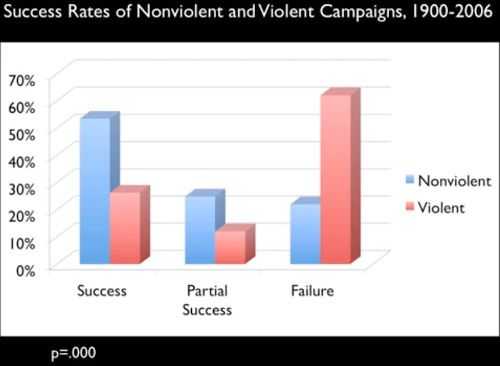

So the next two years she put together data from every political campaign, both non-violent and violent and compared the results of each.

This is what she found.

Peaceful campaigns were significantly more likely to succeed at their aims than violent ones. Not only this, as culture changes the effectiveness of violent campaigns decrease. That is; with the passing of time, we are becoming less and less responsive to force. Today, violent takeover is as ineffective a strategy as ever.

To me, this isn't very hard to see.

When the police arrested George Floyd for the ludicrous charge of allegedly counterfeiting a twenty-dollar bill, he was manhandled and abused — yet he didn't so much as raise a finger in response. If you haven't seen the footage yet, it is online for all to see. He doesn't even so much as provoke them with his words. Even when he was dying beneath the weight of officer Chauvin there was only pleading, no malice. Among his final utterances, he was calling for his mother.

Is it so difficult to see how his passivity is what stirred our emotions and provoked this global response? Would the denizens of the world feel such a visceral sense of injustice if he started a fight with them or even if he simply fought back?

The effectiveness of Non-Violent resistance was first utilised formally by the famed Mahatma Gandhi considered a saint in India. Gandhi was a very clever man; he wasn't anything approximating a hippie — he embraced non-violence as an effective means to social change.

Tyrants depend on lies, propaganda and uncertainty to control the masses at large.

When those assaulted do not retaliate in any of the usual ways, it becomes increasingly difficult to paint them as the villain. The narrative of justified violence that the authorities depend on upon become impossible to swallow.

We all know that Martin Luther King had a dream. What most of us didn't realise is that he had a plan — and an excellent one at that. His non-violence was a practical means to achieve his political goals. In fact, his inspiration was none other than Mahatma Gandhi himself.

"Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity."

Dr Martin Luther King

People well-intentionally paint Mahatma Gandhi and Dr King as dreamers who dared to pursue their high-flying ideals and stick with them to the end. I believe this is mistaken. For those confused, blinded by their own cynicism, pursuing non-violence appears to be an act of faith — but this is far from the case. Gandhi and Dr King were as wise, pragmatic and intelligent as any leader of the time — their pragmaticism demanded their commitment to peace. They were not hopeless dreamers at all, but wise leaders capable of seeing reality through the widest of lenses.

There's an optical illusion here: when one cannot see the rationale behind it, the highest pragmaticism appears indistinguishable to wildest idealism.

When asked about Mahatma Gandhi, the mischievous guru Osho[^2] responded:

"He was the most cunning politician the world has ever known."

Conversely, asked about Adolf Hitler:

"He was the most idiotic politician the world has ever known."

Watch the entirety of this exchange here. It is incredibly amusing.

Hitler played a game where it was guaranteed that the world would rise as his enemy. Gandhi made friends with the world from the outset, and he openly declared his disinterest in harming those who would otherwise rally against him.

The two extreme responses to adverse political circumstances are:

- Submit to the violence, to coercion, to that which causes needless suffering

- To retaliate with more violence and coercion and thereby produce more needless suffering

The great middle way in between the two is to be fiercely non-cooperative with the behaviours and structures than inflict suffering on others, yet unwilling to cause more suffering in the name of peace. In the case where perfect disobedience is untenable, then to whatever degree is, to whatever capacity we can. Merely refusing to contribute to the problem is all that is needed. It is it not doing something but refraining to partake in that which causes suffering.

We live in a world where many resort to violence and coercion because it can be efficacious in getting people to do what you want. This is not a constant, but a variable. If we all refuse to bend, to submit whenever anyone tries to get their way by force, coercion as a strategy weakens.

On the contrary, to fight oppression with force is to accept the efficacy of violence — in fact, it is to count on it.

I believe Gandhi realised this, and I believe Martin Luther King knew this. War was never a checkpoint on the path to peace.

Back to the analysis of historical findings of Erica Chenoweth:

- Peaceful protest has been significantly more successful than violent protest

- Over time the efficacy of peaceful protest has increased, and that of violent protest has decreased

We are already learning to refuse to cooperate with those who would have our way with us. We are already developing a distaste for violence, for being told what to do. War was once considered glorious; now it is viewed as evil, and there will come a day where we see it for the stupidity it is.

Racism is the very same. At its base, it is nothing more than a misconception, the belief that people are inferior or otherwise less worthy of proper treatment by the colour of their skin. The demon that we have been preparing to face has been none other than stupidity itself.

The reason we know that the way forward is peace is because we peered into the past and have learned from it. On the contrary to our progress being contingent on denying the successes of the past, it depends on it.

Okay, I am feeling tired. That was a long letter. In fact, it is the longest letter I have ever sent out. I have hit a record here, at this moment I have over four thousand words. You might have noticed that this is in your inbox later than usual, that's because it took me a few days to write this one.

If you are one of the people that have read all the way here, I am truly grateful for you. Writing this piece has bourne fruit. I sincerely hope you have enjoyed it and that you are getting value from these.

Also, it seems that since lockdowns have been happening and I have not been going to social events and meeting new people, the growth of my subscribers has stagnated. There have been around a hundred for a very long time. If you know anyone that would enjoy this or any piece, please share it with them. I write my thoughts so that they may be read and benefit others, after all.

I hope all of you find happiness amid all the chaos.

Stay well,

Sashin

Discussion