Hello everyone,

Welcome to the new decade — I hope it's been pleasant for you so far!

I have already been busy this year, preparing the future of my reading, learning and writing adventures. I have plans to write about a whole slew of new topics, expand the website and increase my reach.

Amidst my excitement, there has been something that has been bothering me. That is; the state of the internet.

A tremendous waste of time

Tristan Harris has been called "the closest thing silicon valley has to a conscience". He has been concerned about a behemoth of a problem that is completely off-the-radar for most of us. That the social platforms we use on a day-to-day basis have been designed to waste our time.

Watch this video to get a picture of the problem (~4 minutes):

Tristan is the co-founder of The Centre of Humane Technology, an organisation dedicated to realigning the way our technology is designed to serve our deepest values.

Facebook draws in over fifty billion dollars in revenue in a year, yet we the users do not pay a cent.

Why is this?

Because we aren't really the users, we're the product.

Facebook is an advertising company. If you have a message that you want to reach the denizens of the internet, simply pay them and they will expose them all to it.

The more time we users spend on the platform, the more likely we are to click on an ad. Therefore, the interface we engage with and the algorithms that serve us content have been tailored to keep us there.

But the worst part is that I know this is what's going to happen, and even knowing that's what's going to happen doesn't stop me from doing it again the next time. Or I find myself in a situation like this, where I check my email and I pull down to refresh, But the thing is that 60 seconds later, I'll pull down to refresh again. Why am I doing this? This doesn't make any sense.

But I'll give you a hint why this is happening. What do you think makes more money in the United States than movies, game parks and baseball combined? Slot machines. How can slot machines make all this money when we play with such small amounts of money? We play with coins. How is this possible? Well, the thing is ... my phone is a slot machine. Every time I check my phone, I'm playing the slot machine to see, what am I going to get? What am I going to get? Every time I check my email, I'm playing the slot machine, saying, "What am I going to get?" Every time I scroll a news feed, I'm playing the slot machine to see, what am I going to get next?

An excerpt from Tristan's 2014 TED Talk in Brussels

We are only human. We are fallible and we can be persuaded. When products are designed explicitly to suck us in, we are going to give in.

We aren't even having enjoying ourselves. Maximising screentime is not the same as maximising happiness. We are not spending time like this because we are having a blast, and we tend not to be happy with ourselves when hours fly by. Coming back to the analogy of the slot machine, can you say that the people sitting there for hours are having a peak experience? Are they even having a good day?

Our lives are fleeting, death draws nearer by the minute. How many more moments do we want to live in meaningless distraction?

Given the heights of happiness the human psyche is capable of experiencing, is this not an abject waste of life?

Choice architecture: Broken by design

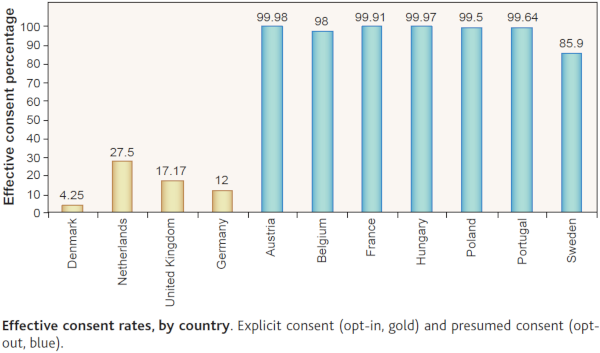

Take a good look at this graph (source).

Here you can see the percentage of citizens in each of the countries in Europe who have consented donate their organs after death. There are two very distinct groups here. The countries that almost entirely opt-in to donate their organs and those that almost entire refrain.

What is the difference between them?

Is it culture? No.

It is simply the form that they fill.

The countries on the left all have opt-in forms — they have to tick a box to sign up for the donation program.

The countries on the right all have opt-out forms — they have to tick a box to abstain from donating their organs after death.

This example is from the wonderful Dan Ariely's TED Talk: Are we in control of our own decisions.

Another classic example of choice architecture is the positioning and display of products in the store. Many bottleshops stock expensive wine, that almost no one buys and display them alongside their popular options. Why is this?

Because we compare our choice with the other possible options. Even though people do not tend to buy the most expensive wine, having it on display makes it more likely they will buy the second most expensive. Most people tend not to want to choose the cheapest or the most expensive option after all.

Charities are well-known for designing their forms with default options that nudge the consumer into choosing higher amounts than they would otherwise.

Supermarkets have been traditionally designed to have the essential items (bread, milk and eggs) far away from one another, forcing to walk through the shop and increasing the chance we are tempted to buy unnecessary items.

At the end of this heroic journey we run into even more temptation at the checkout — why do we make it so easy to make the choices that we regret?

Our digital platforms are all the same.

-

YouTube will use algorithms to determine which video is most likely to keep you watching, and it will autoplay it by default.

-

Twitter intentionally adds a moment's delay between loading, and revealing how many notifications you have to increase that sense of anticipation and the dopamine that goes with it.

-

Netflix discovered that customers using the service for less than a certain number of hours were likely to cancel so redesigned their interface to increase the likelihood users will watch the next episode (and often delay working, eating and sleeping to do so)

-

Snapchat introduced a particularly insidious feature known as "Snap Streaks", where users are encouraged to build streaks by engaging with the same friend each day. This uses social pressure to manipulate people to stay on the platform — you wouldn't want to ruin your friend's streak, would you? (also consider that the bulk of Snapchat users are teens)

By designing the interface, we can influence the decision that people make. We can do this to their benefit or their detriment.

What determines this, is whether the incentives of the designer are aligned with the happiness of the user. When the design is driven to maximise the time spent on the platform, the result is unnecessary distraction and a tremendous waste of time.

Our lives are nothing but the moments in them; when we waste our time, we waste our lives.

Aside: A Spark of Joy

A few weeks ago I finally got around to cleaning my room for the first time in a while. My room is usually pretty clean — I don't have that much stuff — but after a while it gets dusty. To make the activity fun, I thought while cleaning I would finally listen to Marie Kondo's The life-changing magic of tidying up.

Rather than spending half-an-hour tidying up, I spent the whole day going through all my possessions and purging them all. The end result was a very clean room and a very good time.

For those of you that don't know the patented KonMari method involves taking each and every possession you own, picking it up and asking yourself "does it spark joy?"

Only the possessions that truly spark happiness within are retained and everything else is thrown out. The end result is a space in which everything makes you happy.

This part of the book talking about clearing up your bookshelf in this way, had me glowing with happiness:

"Imagine what it would be like to have a bookshelf filled only with books that you really loved. Isn't that image spellbinding?"

A thought came through my mind at this point:

"Why stop at books, clothes or even possessions?"

Our ambitions, our desires, our activities, our experiences, our habits (both physical and mental) and every aspect of ourselves and the lives we lead. Why not take them all into our hands and ask "does it spark joy?"

Why not aspire to a life in which every moment was happiness?

The Arms Race for Attention

This was actually said by Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix (source):

"At Netflix, we are competing for our customers' time, so our competitors include Snapchat, YouTube, sleep, etc."

They are competing with sleep.

Are you familiar with the idea of a nuclear arms race?

- America doesn't want to build nukes, but they have to because Russia is.

- Russia doesn't want to build nukes but they have to, because America is.

- China doesn't want to build nukes, but they have to because America and Russia is.

And so on, so forth until now we have enough nukes to wipe out civilisation many times over and do not know what to do with them.

The lifeblood of the online services that have become a staple in our lives is our attention. What they want is for us to spend our time engaged on their platforms — but is this what we want?

Netflix, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram and all the characters you know and love are competing for our attention. The more time we spend on each platform, the more likely we are to click on ads and the higher their bottom line is.

If one of the platforms is designed to be extremely addictive and sap away our time and attention, the other platforms need to follow suit to remain in the game. To remain competitive in the digital world each of the platforms is forced to be addictive by design.

What is more perverse is that the very designers themselves do not like what they are doing. As Tristan says, they lament they come home from work to children addicted to the very platforms they helped build.

Reclaiming our lives

Tristan's initiative to realign the incentives of our technology with our deepest desires is called Time Well Spent. At the moment our digital platforms have been designed to keep us there, to drain away our time and attention.

But what if we designed it to maximise the happiness of its users, rather than the time spent on the platform?

What if the algorithms were designed to serve us the most timely and relevant information to achieve our goals rather than distract us away from them?

What if our designers from the start influenced our behaviours to facilitate meaningful connections and positive experiences, rather than just maximised screen time?

What if the efforts of our software engineers helped us reflect on our day as time well spent?

There is no reason in principle this can't be done.

To learn more about Tristan Harris and his efforts, please watch his TED Talks:

- How better tech could protect us from distraction

- How a handful of tech companies control billions of minds every day

When I first read the analogy of refreshing your social media feed as a slot machine, I was struck by familiarity. So I decided to do something about it, wondering what would Tristan do?

Conveniently, the answer is on his website.

Click here to read his recommendations on how to take back more control from your devices.

I am using an android phone and am running Firefox on my laptop, so I can share advice relevant to those platforms.

On my phone, I use a home screen called Siempo which offers a minimalist phone experience with nudges away from distractions and addicting apps. It includes. This makes it harder to access the distracting apps and easier to access the useful ones — freeing up more of your time. It also sets the screen to black-and-white in the evenings and early mornings which makes the phone less compelling to use. It has a whole host of other features as well which make the phone experience more pleasant and less like a slot machine.

There is an interface installed by default on Android called "Digital Wellbeing & parental controls", accessible from the settings. Here you can see how many times you have unlocked your phone in the day, how much time you've been on it and which apps have been using your time. At the end of the day, I have been looking at it and contemplating if I have been wasting my time. If the time I've spent on my meditation app is more than on social media, I feel quite happy with my day.

On Firefox there is an extension called Shift by Siempo, which in essence does the same as the phone app. Making distracting sites harder to access, it is less likely that you will do so out of habit but rather for a purpose (as you have to think before opening them).

For those of you that use twitter, I recommend you use the tool — Tokimeki Unfollow.

Tokimeki (ときめき) is the Japanese word that has been translated to mean "spark joy", this tool helps you purge your twitter timeline of content that does not make you happy. You go through the tweets of everyone you follow and ask "do these spark joy?"

With a timeline with only tweets that elicit happiness, the time you spend on it is more likely to be time well spent.

This letter is the first of a series I will be starting around the theme "fixing the internet" — for this isn't all that is wrong with it. I have been thinking about these problems for a while, and as a content creator, I can see them from a completely different perspective. Issues in general that I will be covering include the problems with the advertising model, the widespread misinformation that the internet enables and how it impacts our culture and politics.

As this is new terrain for me I would love to hear from you, how did you find the experience of reading this letter? Was it time well spent?

There is a real person behind this address, please feel free to reply to this and let me know all of your thoughts. I always love hearing from readers.

Thank you for reaching the end of yet another letter, I hope you are all doing well and that every moment of your life helps spark joy.

Stay happy,

Sashin

Discussion