Hello everyone,

I trust you are all well. At the very least, you are well enough to have the leisure of reading this letter. It is a good start — contemplate for a moment how many people are living right now that do not have this luxury?

I want to cut right to the chase, in today’s letter I will be talking about a phenomena that has been annoying me for quite some time; Cynicism.

They don’t make it like they used to

Cynicism (Ancient Greek: κυνισμός) is a school of thought of ancient Greek philosophy as practised by the Cynics (Ancient Greek: Κυνικοί, Latin: Cynici). For the Cynics, the purpose of life is to live in virtue, in agreement with nature. As reasoning creatures, people can gain happiness by rigorous training and by living in a way which is natural for themselves, rejecting all conventional desires for wealth, power, and fame. Instead, they were to lead a simple life free from all possessions.

From Wikipedia

I want to make clear from the outset, this is not what I am talking about.

Much like with the word “stoicism”, the contemporary use of “cynicism” is far removed from its origins in Greek philosophy. No longer having anything to do with leading a life of virtue, we now take stoicism to mean not displaying your emotions and we equate cynicism with a negative outlook, that is; pessimism.

They don’t make cynicism like they used to.

From the Oxford dictionary:

- Cynicism

-

- An inclination to believe that people are motivated purely by self-interest; scepticism. ‘public cynicism about politics’

- An inclination to question whether something will happen or whether it is worthwhile; pessimism.

In essence, I want to talk about the two types of cynicism in modern discourse. The tendency to believe that other people and their intentions are ultimately bad and that the world as it is, our current state of affairs is so. The kind of cynicism I tend to see is even deeper than this, though. It is not merely pointing out that there are severe problems with the way things are, but the felt conviction that they are unsolvable. As if the ails we experience were inherent to human nature, or even fundamental to life itself.

It is this cynicism that I would like to contend with.

A Motte, A Bailey and A failure to make a point

Have you heard of the term motte-and-bailey?

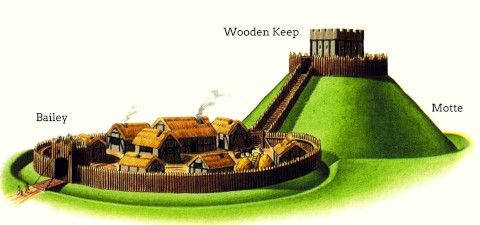

The above is an image of a Motte-and-Bailey castle. There are two parts; the stone tower elevated on the mound known as a motte and the main courtyard at ground level known as a bailey.

The motte is the final defence and is reserved usually for the supposedly most important individuals, the lord and lady of the castle along with their family. The bailey is where the main population lives.

The motte here, being elevated above ground level and protected by a stone keep is easy-to-defend.

The bailey, being almost out in the open, is vulnerable and harder-to-defend in comparison.

The motte-and-bailey fallacy is a form of argument where a person conflates two different positions which are superficially similar. One of them is more-or-less common sense — it is easy to defend, but isn’t saying much, the other is striking and controversial and very difficult to defend.

For example:

- (Motte) There are problems in the world

- (Bailey) The world is a bad place and is getting worse

“The world is such a terrible place, look at what it is happening, everything is getting worse.”

“What do you mean? We’ve been making so much progress. We’re improving by almost every metric we value; life expectancy, level of violence, deaths by preventable illness, wealth and self-reports of happiness.”

“Yes but we still have problems x, y and z”

Here we have someone making a sweeping yet insubstantial claim; the bailey, and when they are challenged, they retreat to a more secure foundation; the motte. Worse still, at junctures like this, many will continue to proclaim belief in the bailey and even influence others to adopt it. The cycle repeats, when they are challenged on the bailey they fallback on the motte.

The use of a motte-and-bailey fallacy in my view is remarkably common and is often one of the main ways we hold our ideas immune from criticism and maintain our misplaced beliefs.

Cynicism ≠ Skepticism

One conflation that I have seen many times that bothers me; people continually confuse cynicism and skepticism.

- Sceptism

- A sceptical attitude; doubt as to the truth of something.

Skepticism is a questioning attitude. It is not holding false certainties and not believing propositions in the absence of reason and evidence.

Cynicism is conversely almost a conviction that the world as we know it is bad and the motivations of our fellow humans is sinister, often irreparably so.

The claim that you should question conventional wisdom and be slow to regard information as fact is not the same as saying that the world is a bad place and that we are untrustworthy by nature.

Please know that the two are not the same.

Skepticism is a virtue. Cynicism is a vice.

Skepticism is to refuse to be certain in the absence of reason.

Cynicism is to hold the conviction that the world or the people in it are bad.

Cynicism is espoused, skepticism defended.

Skepticism is the motte. Cynicism is the bailey.

It is not realism

I am not sure if anything quite bothers me as much as when someone starts a sentence with “I’m a realist” as if it added anything to their case. Newsflash: We are all trying to see reality as it is.

They might as well be more direct and say “I think you are delusional”.

“Optimism has come to mean that the assumption that the best will happen, or probably will.

Pessimism is the assumption that the worst will.

They are both false as general principles. No one adopts them.

The are irrationalities that everyone accuses each other of.”

David Deutsch on Optimism

I never tend to call myself an optimist. I simply speak as if the problems we see can be solved. That there are ways that we can mitigate the bad, and I even propose ways of doing so. What happens is by holding these views I get labelled an optimist by others — and criticised for not being realistic.

I want to see reality as it is.

As far as I can see, we can solve problems and we can improve our state of affairs. We have done it before, and I believe we can do it again. It is worth trying to do this. I do not claim that the best is inevitable or even probable. The cynics that I encounter certainly seem to be claiming this with the worst.

I feel as if I have uncovered a new logical fallacy: Argumentum ad Optimism

The argument that a proposition is absurd because it would be too good if it were true.

But what does how good an outcome is, tell us anything about how likely it is? Are you trying to see the world as it is? Or are you merely trying to protect yourself from potential disappointment?

“In fact, both ends of the spectrum and the middle, are predictions of success or failure, derived only from an attitude or a principle, and not from explanation of why reality should match them.

And prediction without explanation is prophecy.”

David Deutsch, from the same video as the above quote

Predicting the future from the ideal of optimism is irrational. Predicting the future from the view of pessimism is irrational. Predicting that it must be in between — that it is neither the best or worst outcome — is also irrational.

A prediction based on anything apart from an explanation of why it would be true is tantamount to prophecy.

Once again; how good or bad and outcome would be if it were true, has nothing to do with whether it is true.

One thing that astonishes me about the conviction of many self-proclaimed cynics is how they persist in their view that the world cannot improve. There is a conviction that we cannot improve our state of affairs. We are quick to criticise modernity, but in almost every measure we can observe we are doing better than we have ever before.

It is the work of the excellent Steven Pinker that first cemented this into my mind.

In 2011, he published the best-selling book The Better Angels of Our Nature which details the continual decline of violence throughout the history of civilisation and discusses theories as to what the reasons behind them were. Bill Gates has called it his number-one book recommendation.

Since then, in 2018 he has published another best-seller Enlightenment Now which takes the case beyond violence. It is not merely that we have grown more peaceful over time, but we have improved our lives in pretty much every way we can conceive. Bill Gates has called this his new all-time favourite book.

I’ve written about it before. Let me share with you again, my favourite part of the book.

An Excerpt from Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now

Since the Enlightenment unfolded in the late 18th century, life expectancy across the world has risen from 30 to 71, and in the more fortunate countries to 81. When the Enlightenment began, a third of children born in the richest parts of the world died before their fifth birthday; today, that fate befalls 6 percent of the children in the poorest parts. Their mothers, too, were freed from tragedy: one percent in the richest countries did not live to see their newborns, a rate triple that of the poorest countries today, which continues to fall. In those poor countries, lethal infectious diseases are in steady decline, some of them afflicting just a few dozen people a year, soon to follow smallpox into extinction.

The poor may not always be with us. The world is about a hundred times wealthier today than it was two centuries ago, and the prosperity is becoming more evenly distributed across the world’s countries and people. The proportion of humanity living in extreme poverty has fallen from almost 90 percent to less than 10 percent, and within the lifetimes of most of the readers of this book it could approach zero. Catastrophic famine, never far away in most of human history, has vanished from most of the world, and undernourishment and stunting are in steady decline. A century ago, richer countries devoted one percent of their wealth to supporting children, the poor, and the aged; today they spend almost a quarter of it. Most of their poor today are fed, clothed, and sheltered, and have luxuries like smartphones and air-conditioning that used to be unavailable to anyone, rich or poor. Poverty among racial minorities has fallen, and poverty among the elderly has plunged.

The world is giving peace a chance. War between countries is obsolescent, and war within countries is absent from five-sixths of the world’s surface. The proportion of people killed annually in wars is less than a quarter of what it was in the 1980s, a seventh of what it was in the early 1970s, an eighteenth of what it was in the early 1950s, and a half percent of what it was during World War II.

Genocides, once common, have become rare. In most times and places, homicides kill far more people than wars, and homicide rates have been falling as well. Americans are half as likely to be murdered as they were two dozen years ago. In the world as a whole, people are seven-tenths as likely to be murdered as they were eighteen years ago.

Life has been getting safer in every way. Over the course of the 20th century Americans became 96 percent less likely to be killed in a car accident, 88 percent less likely to be mowed down on the pavement, 99 percent less likely to die in a plane crash, 59 percent less likely to fall to their deaths, 92 percent less likely to be asphyxiated, and 95 percent less likely to be killed on the job. Life in other rich countries is even safer, and life in poorer countries will get safer as they get richer.

People are not getting just healthier, richer, and safer but freer. Two centuries ago a handful of countries, embracing one percent of the world’s people, were democratic; today, two-thirds of the world’s countries, embracing two-thirds of its people, are. Not long ago half the world’s countries had laws that discriminated against racial minorities; today more countries have policies that favor their minorities than policies that discriminate against them. At the turn of the 20th century, women could vote in just one country; today they can vote in every country where men can vote save one. Laws that criminalise homosexuality continue to be stricken down, and attitudes toward minorities, women, and gay people are becoming steadily more tolerant, particularly among the young, a portent of the world’s future. Hate crimes, violence against women and the victimisation of children are all in long-term decline, as is the exploitation of children for their labor.

People are putting their longer, healthier, safer, freer, richer and wiser lives to good use. Americans work 22 fewer hours a week than they used to, have three weeks of paid vacation, lose 43 fewer hours to housework, and spend just a third of their paycheck on necessities rather than five-eighths. They are using their leisure and disposable income to travel, spend time with their children, connect with loved ones, and sample the world’s cuisine, knowledge and culture. As a result of these gifts, people worldwide have become happier. Even Americans, who take their food fortune for granted, are “pretty happy” or happier, and the younger generations are becoming less unhappy, lonely, depressed, drug-addicted, and suicidal.

As societies have become healthier, wealthier, freer, happier, and better educated, they have set their sights on the most pressing global challenges. They have emitted fewer pollutants, cleared fewer forests, spilled less oil, set aside more preserves, extinguished fewer species, save the ozone layer, and peaked in their consumption of oil, farmland, timber, paper, cards, coal and perhaps even carbon. For all their differences, the world’s nations came to a historic agreement on climate change, as they did in previous years on nuclear testing, proliferation, security, and disarmament. Nuclear weapons, since the extraordinary circumstances of the closing days of World War II, have not been used in the seventy-two years they have existed.

Nuclear terrorism, in defiance of forty years of expert predictions, has never happened. The world’s nuclear stockpiles have been reduced by 85 percent, with more reductions to come, and testing has ceased (except by the tiny rogue regime in Pyongyang) and proliferation has frozen. The world’s two most pressing problems, then, though not yet solved, are solvable: practicable long-term agendas have been laid out for eliminating nuclear weapons and for mitigating climate change.

For all the bleeding headlines, for all the crises, collapses, scandals, plagues, epidemics, and existential threats, these are accomplishments to savor. The Enlightenment is working: for two and a half centuries, people have used knowledge to enhance human flourishing. Scientists have exposed the working of matter, life, and the mind. Inventors have harnessed the laws of nature to defy entropy, and entrepreneurs have made people better off by discouraging acts that are individually beneficial but collectively harmful. Diplomats have done the same with nations. Scholars have perpetuated the treasury of knowledge and augmented the power of reason. Artists have expanded the circle of sympathy. Activists have pressured the powerful to overturn repressive measures, and their fellow citizens to change repressive norms. All these efforts have been channeled into institutions that have allowed us to circumvent the flaws of human nature and empower our better angels.

The world has clearly improved time and time again. We have enhanced our way of living by almost every metric we can conceive. It does not logically follow that therefore improvement is inevitable. As we are all living through the COVID-19 pandemic, I hope you know that curves can flatten.

However, it does seem to follow that progress is possible. There are no deep reasons why we can’t solve the problems in the world and improve our circumstance. Time-and-again throughout history, we have sought to better the world we have found ourselves in, time-and-again we have succeeded.

We have done it before, and we can do it again.

The Mechanics of Cynicism

In my view; the cynical attitudes many of us have manifested is a failure to reason honestly with ourselves. Far from being insight into the way things are, or wisdom gained through experience, I view it as a defensive mechanism. A crutch to lean on. A means of protecting oneself from potential disappointment.

We do not sink into these lows because we are brave enough to face the cold truth, but because we are afraid to walk into an uncertain future. It is more comfortable to reassure ourselves that the world and the people in it are wicked, than to consider that they are a mystery. We pretend we know that the outcome will be adverse and brace ourselves, hardening our hearts in its anticipation — rather than realise that we indeed don’t know how things will play out. Somehow it is easier to bear telling ourselves that the worst is certain, than that there is genuine uncertainty in our circumstance.

The emotions that follow do not serve us, as the sage Shantideva has taught us:

If there’s a remedy when trouble strikes,

What reason is there for dejection?

And if there is no help for it,

What use is there in being glum?Chapter 6, Stanza 10, The Bodhicharyvatara

What’s more is that in almost every way, when looking at trends over time, the world improved. We are doing better than we have ever done before.

Good and bad are at heart relative terms; they are a way of comparing some circumstances to others. We are not comparing the world we live in with any real world that we have seen in the past. We are comparing it with an imaginary world of our ideal.

Even if our lofty ideals were realised, could we not again dream up ever more lofty peaks? Will not the constant comparison with the imaginary give us license to forever wallow in cynicism? It is always possible to imagine a better world, but being miserable does not help actualise it.

Sam Harris in his app Waking Up has talked about life as a problem-solving process. That we often tacitly imagine that we can solve all our problems and reach a stable state of peace in the future. As if we could clear our to-do list for good. But as sure as problems are solvable, they may be inevitable. If we postpone that enjoyment of our lives — our happiness — until after our problems are solved, it will vanish like a mirage. We must learn to enjoy the problem-solving process — the perpetual growth in our knowledge and the continual betterment of our world. Life is nothing but this process.

He even goes as far as to remark if a problem-free life is even desirable? When we play a video game, why is it we never choose to play the easiest level over and over again? What is it that we honestly want out of life?

The way things are is the way things are. How different could they be? We can improve this world, but to expect that it should have been, that it could have been some other way is unjustified. The other way is ultimately a figment of our imagination. We compare reality to a standard of our creation, as if we were in a place to judge it.

I will leave you with a snippet from Herman Hesse ’s spiritual fiction Siddhartha.

“Therefore, I see whatever exists as good, death is to me like life, sin like holiness, wisdom like foolishness, everything has to be as it is, everything only requires my consent, only my willingness, my loving agreement, to be good for me, to do nothing but work for my benefit, to be unable to ever harm me.”

“I have experienced on my body and on my soul that I needed sin very much, I needed lust, the desire for possessions, vanity, and needed the most shameful despair, in order to learn how to give up all resistance, in order to learn how to love the world, in order to stop comparing it to some world I wished, I imagined, some kind of perfection I had made up, but to leave it as it is and to love it and to enjoy being a part of it”

Diogenes the Cynic cared not for material pleasure, financial security or the goods that the world offered. He voluntarily lived in homelessness. He sat in the roadside free of concern; his only dwelling place was the intrinsic bliss of his mind.

One day the King — Alexander the Great — passed by and decided to amuse himself with the sage.

“Today is your lucky day, I will grant you whatever you desire. Simply state your wish, and I will use my power as King to make it a reality.”

“Can you move a little to the side? You are blocking the sun.”

Almost everything we could care for in the world has improved, but what we mean by cynicism has sorely plummeted. We don’t make cynics like we used to.

If you are reading this, then you are one of the few to come to the end of another letter.

Thank you for reading. I hope you have enjoyed this and that you are deriving benefit here.

Some news, I was a little worried I might have been inaccurate with a letter I sent out a few weeks — The Beginning of it All.

In it, I tried to narrate the sequence of cosmic events from the Big Bang to now and explain the reasons why we believe this is how it all came to be.

As I am not an Astrophysicist, I decided to hire one to read over my work and check to see if it matched what they know. To be more precise, I hired the wonderful Kirsten Banks.

There were indeed two mistakes I made in the piece; they were not too consequential and didn’t change the overall message of the piece.

Click here and scroll to the bottom of the letter if you would like to read about them.

Once again, thank you for your interest in what I have to say. It is because of you that there is meaning in what I write.

Please take care,

Sashin

Discussion